Does Higher Turnout in Florida Increase Democratic Votes?

BY JAMES G. KANE

Conventional wisdom among political pundits and the media takes as fact that higher turnout always increases the Democratic share of the statewide vote.

“The Florida governor’s race was supposed to be about turnout. It was,” said the American Spectator (Nov. 7, 2014). “Democrats have won the past two presidential races in Florida, but low Democratic turnout in midterm elections has helped Republicans win the past four governor’s races” said the Tampa Bay Times (Nov. 4, 2014).

This assumption is based on the reasonable premise that Republican voters are better educated, better informed and usually more attentive to campaign affects, and consequently, participate at higher levels even in lower level elections. Democrats, on the other hand, are younger, less educated and less politically involved than their Republican counterparts. As a result, Democratic voters participate less, particularly in lower level and less competitive elections.

This theory posits that as election turnout rises, the number of Democratic voters’ increases as well, thus elevating the Democrat candidate’s chances of winning. Taking liberty from a famous proverb, we could say “a rising turnout lifts all Democratic votes.”

In recent research, however, this conventional view has recently come under reevaluation by political scientists (as an example see “Rethinking the partisan effects of higher turnout: So what’s the question? Grofman, Owen and Collet, Public Choice, June 1999.)

At best, the empirical evidence that increased turnout benefits the Democratic vote is mixed, depending on the time period, the type of analysis and, especially, whether the election is Presidential or midterm (elections prior to 1965 may have followed this pattern outside the south (see Nagle and McNulty, “Partisan Effects of Voter Turnout in Senatorial and Gubernatorial Elections,” American Political Science Review, December 1996)).

In the 2014 Gubernatorial Election, incumbent Rick Scott defeated Charlie Crist by a one percent and the turnout was only 50.1% .

In 1994, incumbent Lawton Chiles defeated Jeb Bush by 1.6% and the turnout was 66%.

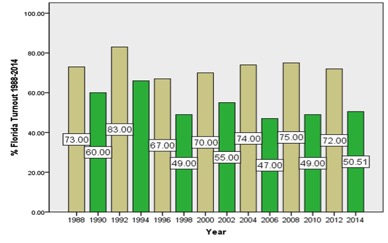

The question, of course, would Charlie Crist have defeated Rick Scott if turnout had been higher? Before we try to answer this question, let’s start with the turnout difference between Presidential and midterm elections. Figure 1 displays the turnout rates of all elections since 1988.

Figure 1

In the 14 years covered in this graph, the average turnout (among registered Florida voters) for midterm elections was 19.6% less than Presidential years. That midterm turnout is always lower than Presidential election years is no surprise to anyone, but the decline from Presidential turnout has certainly become more severe in recent years than in the past (at least since Florida became a two party state). Figure 2 shows only the midterm turnout without Presidential years to emphasize this recent decline.

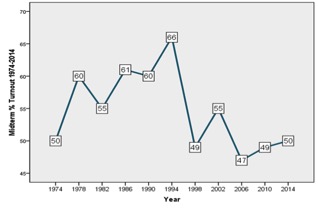

Figure 2

Beginning in 1998, when Jeb Bush defeated Buddy McKay, midterm turnout took a noticeable drop in voter participation. Why this occurred, is not the subject of this article, but I will focus on this decline in a later commentary. But it is obvious that a significant change has occurred. But the emphasis here is on whether this decline has also contributed to the defeat of Democratic Gubernatorial candidates, as suggested by both the media and political commentators.

[Author’s note: The following analysis is based on what researchers call a time series of aggregate data, which means that observations are not of individual voters and, consequently, are not randomly selected as with individual survey data. But Florida turnout can only be measured at the individual level with survey data over time, and such surveys do not exist. Consequently, aggregate data can show a causal relationship at the aggregate level but not at the individual level. In this case, we don’t consider individual voters’ intentions to vote, but only the results of their group actions.]

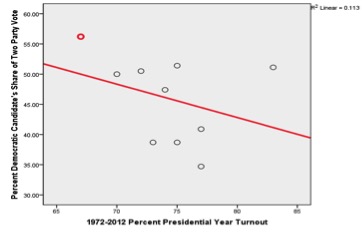

Our hypothesis, simply put, is that as statewide turnout rises so does the Democratic share of the vote increase as well (I will address the South Florida difference in a later article). If turnout does increase the Democratic share of the vote we should see a statistical relationship when compared to previous elections. But first we must separate the Presidential elections from midterm years so we don’t confound the results. Since Presidential turnout is usually significantly higher, we should see a relationship between the Democratic two party share of the vote and turnout. In Figure 3, I display a scatterplot of the correlation between a Democratic Presidential candidate share of the two party vote and turnout since 1972.

Figure 3

The X axis (the horizontal axis) has the turnout ranging from 65% to 85% and the Y axis (perpendicular axis) ranges from 30% to 60% of the Democratic candidate’s vote share. Each dot on this scatterplot represents a particular presidential election and the red line is a regression line showing the linear relationship between the Democratic candidate’s share of the two party vote and turnout. The regression line slopes downward indicating that as turnout increases the percent of the Democratic candidate’s two party vote decreases as well. The negative correlation coefficient (-.337, ns) confirms this association. Interestingly, the red dot located in upper left hand corner of the figure, represents the two-party share of the vote for Bill Clinton in 1996, when he defeated Bob Dole by over 5% with the lowest turnout in this time period. This is obviously an “outlier.”

This relationship, of course, is counterintuitive but neither the R square statistic nor the correlation coefficient is significant, meaning the association is not reliable. In other words, this correlation does not indicate that as turnout increases the Democratic Presidential candidate’s vote decreases. But what it does demonstrate is that increased turnout does not increase the Democrat’s vote in Presidential years. In the case of Presidential elections at least, our hypothesis is null.

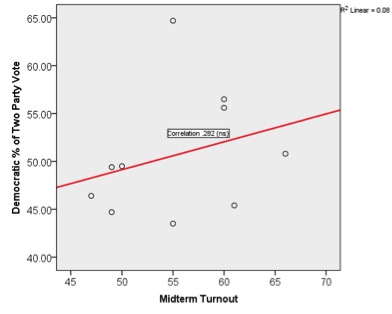

So the next question is “what about midterm turnout?” As pointed out, many have suggested Charlie Crist could have won the Governor’s race if only turnout was higher. In Figure 4, we reproduce the same scatterplot but this time with midterm turnout and Democratic candidate’s share of the two party vote, to see if this is case.

Figure 4

Each dot on this graph represents a Florida midterm election from 1974 to 2014, and like the previous chart, the horizontal axis the turnout ranges from 45% to 70%, while the perpendicular axis the Democratic candidate’s share of the two-party vote. As opposed to the previous figure, the regression line slopes upward suggesting that as turnout increases the Democrat’s share of the vote increases slightly. The correlation coefficient (.282, ns) is also positive as well. However, like the Presidential correlation, it is not significant, meaning that even this weak association is unreliable and not to any meaningful relationship.

In other words, increasing turnout does not significantly increase a Democratic candidate’s share of the vote. And again, our hypothesis is null.

So how could conventional wisdom be so wrong, when the premise that increasing turnout strongly suggests that more Democrats are voting, and, therefore, should vote for the Democratic candidate when they enter the voting booth?

I noted earlier, that elections prior to 1965 and outside the South, likely followed this pattern of higher turnout increasing the Democratic vote. Partisan loyalties, particularly among Democrats, have decayed significantly since then (see James DeNardo, “Turnout and the Vote: The Joke’s on the Democrats,” American Political Science Review, June 1980). This erosion of Democratic partisanship has led to far more defections from their party’s choice than those suffered by Republicans (Martinez and Gill, “The Effects of Turnout on Partisan Outcomes in U.S. Presidential Elections 1960–2000,” Journal of Politics, November 2005).

In other words, being a Democrat doesn’t mean you will necessarily vote for the Democratic candidate. Campaigns and messages still matter.

This decline in strong partisanship is compounded by non-Presidential elections, where the lower visibility of races such as midterm gubernatorial campaigns, produce less clear partisan divisions. Finally, the demographic structure of registered voters has changed significantly since 1993. As I will show in a following article, the Democrats’ reliance on minority voters may have benefited their Presidential campaigns but has reduced turnout in more urban areas during midterm elections.

So why did Charlie Crist lose?

The bottom line is that increasing the overall turnout in Florida would likely not have helped him save the day. Spending an extra 50 million dollars, however, might have done the trick…

(James G. Kane is a long-time local political operative and an adjunct professor in the University of Florida Department of Political Science’s Political Campaigning graduate program. For more information on Kane click here.)

February 10th, 2015 at 11:41 am

I told them that the total turnout doesn’t count. Charlie needed to turnout more Ds like the black community and he couldn’t. Too many remembered “Chain Gang Charlie”

February 10th, 2015 at 4:24 pm

Whether higher voter turnout might benefit one party over another is less important to me than elections being decided by a smaller number of people while the vast majority of us sit on the sidelines and do not participate. That is a bad precedent for any democracy. Not voting should be an exception to the rule, not the rule.

February 10th, 2015 at 5:46 pm

All that research just to show that Charlie Crist lost because he didn’t have enough money to compete. Florida Democrats will never have a money advantage or even par money. They can’t raise it because the governor and Legislature are Republican, therefore there is no incentive to special interests to give to Democrats, who can’t pass legislation or regulations on their own. It is a sad state of affairs created when the Republicans tricked the Democrats into redistricting all the black voters into a handful of district, rather than spreading them out in many districts. It instantly turned many swing districts Republican and gave them a huge legislative majority. In governor’s campaigns, the Democrats just haven’t had a good candidate since Lawton Chiles. Is that figured in your research?

February 11th, 2015 at 10:48 am

Lawton Chiles was the last decent candidate for governor period. After he died, governor wins were tilted much more toward money than anything else.

February 11th, 2015 at 11:36 am

Jim,

I think you got it wrong.

The issue for the Democrats is not, as your stats point to, statewide overall voter turnout.

The issue for the Democrats was Democratic voter turnout. Which you did not analyze.

A major component for that was the substandard Democratic ground game—aka GOTV.

The main components of any election are:

Name Recognition

Persuasion (positive you, negative your opponent)

Turnout (My side)

At least a year before this election 90% of the voters knew who Scott and Crist were and how they felt about them.

All that was left was turnout!

The League of Women Voters may care about overall turnout. Parties should only be concerned about their own voters.

As far as outcome is concerned, who votes is equally or maybe more important than how many vote.

Could anyone dispute that if a 150,000 more Black Democrats had voted that Charlie Crist would have won?

Lumping all voters together, as you did, gives one a terrible misunderstanding of why the Democrats lost. It reminds me of the joke about a man with one foot in boiling water and one foot in ice water…so on the average he’s comfortable?

February 11th, 2015 at 6:14 pm

Jeb Bush, Charlie Crist and Rick Scott combined aren’t worthy of wearing Lawton Chiles’ tee shirt.

February 11th, 2015 at 8:13 pm

This is so true…

Republican voters are better educated, better informed and usually more attentive to campaign affects, and consequently, participate at higher levels even in lower level elections. Democrats, on the other hand, are younger, less educated and less politically involved than their Republican counterparts.

February 12th, 2015 at 10:23 am

>> Republican voters are better educated, better informed

Nothing more ridiculous has ever graced these pages

February 12th, 2015 at 10:01 pm

Good essay, Jim.

But I would like to see how turnout by registered Democrats versus Republicans versus Independents changes over midterm versus presidential elections. That would get more directly at several other questions.

Maybe I’ll do that when I get some time.

Kevin.

February 14th, 2015 at 1:12 pm

You want higher turn out? On both sides of the aisle? Simple instead of making that bureaucracy called the BSOE here is a different way of doing elections. Do what the voters did in OREGON the system nothing else just the system,vote by free mail. They are the only state in the union doing it and there voter turnout is 85%….think about that….time to get out of the old tired useless box. Get into the 20th century. Dont tell me about absentee ballots either they cost $1.20 when your per capita income is below $50,000 a year combined incomes $1.20 x 2 is serious money. A study was done right here by the blogger and he proved it works…

February 14th, 2015 at 1:36 pm

As someone who actually WON AN ELECTION as a conservative Democrat in an owerwhelmingly left win District I know turn out is neither here or there in the sense of “numbers”. Elections are based on who voters feel is honest and has THEIR INTERESTS in mind and NOT his or her personal interests. Republicans win when Democrats, Independents, and even Republicans feel the Democratic candidate or interested in THEM and Republicans win when the voters feel the candidate has THEIR interest not the candidates’ personal interests. Carter won when people felt he was interested in the average person, he lost and Reagan won for the same reason. To say this or that segment of the voters are only interested in own interests does a disservice to the voters.