Countering GOP Myth: Hiking Minimum Wage Has No Effect On Jobs

BY JAMES G. KANE

“How would I know what the minimum wage should be? I mean, the private sector decides wages.” Governor Rick Scott

Actually, he’s wrong. The States’ and the Federal Government set the minimum wage and not the private sector.

But we have to forgive Scott’s ignorance, since his income last year was $712,780, that’s $343.68 an hour or 50 times the minimum wage, so I doubt he thinks much about what the current minimum wage should be set at.

The President, however, in his recent State of the Union address, said he wants a minimum wage of $10.10 an hour. The Republicans in the House Chamber could be seen smirking by such a suggestion. After all, the conservative mantra is that increasing the minimum wage equals job loss and hurts low-skilled workers, the very people we are trying to help. And, don’t forget, it also hurts corporate America’s profits as well.

Over the past several weeks, I have reviewed much of the academic literature on how increasing the minimum wage affects low-wage workers, and although the evidence varies depending on the type of analysis, the bulk of it suggests that there is little or no employment reaction to modest increases in the minimum wage, even for employers with a large share of low-wage workers[i].

The most influential of these studies concentrate on the low-wage, low-skilled workers, for the obvious reason that a dollar increase in the minimum wage will have little impact on the skilled worker making a $100,000 a year salary. Minimum wage workers are generally younger, less skilled and educated and consequently, more dependent on hourly wage industries.[ii]

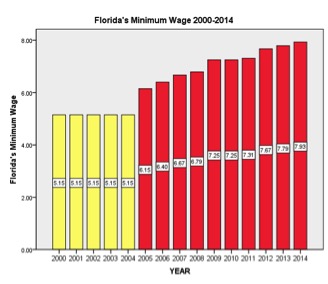

On November 2, 2004, Florida voters approved a Constitutional amendment that increased the state’s minimum wage to $6.15 per hour, a full dollar higher than the Federal minimum wage at the time. In addition, the amendment required the state to index the minimum wage to inflation which is not the case with the Federal minimum wage. As of January, the state established the new minimum wage adjusted for inflation at $8.05, a full 80 cents above the current Federal minimum wage. In Figure 1, I display Florida’s minimum wage over the past 14 years.

Figure 1

The average difference between the Federal and the State’s is 50 cents, with the highest difference being in the second year of the new law at $1.25. A modest difference, of course, but still high enough that it could affect a low-wage earner’s job where, as one fast-food restaurant executive put it, “every penny matters.”

Florida’s minimum wage law provides a real-life experiment in the potential effects that a raise in the wage has as compared to the current Federal requirement. It also allows for the use state-level data that reflects the regional economic differences that are not revealed in national level data.[iii]

In addition, Florida’s new wage law took effect just before the housing-bubble recession that devastated Florida’s economy for nearly four years. Unemployment in the state rose from 3.3% in 2006 to a high of 11.3% in 2009. To my knowledge, this is the first study on a regional minimum wage impact on low-wage earners during a recession.

As I mentioned above, we would expect that the lowest wage earners to be most affected by any increase in the minimum wage. The lowest wage earners are mainly employed in the food preparation and restaurant server positions who do not receive tips. Think of McDonald’s when you order a Big Mac with fries and their employee asks “supersize that for you?” That’s the employee I’m talking about.[iv]

These are the workers who, of course, most need a reasonable minimum wage and the most likely to lose their job if the government raises it, at least according to most conservative economists. It also seems reasonable, that during a recession, these vulnerable workers would be the first to go out the door. Consequently, increasing the minimum wage during a recession should be a double-whammy for these folks hanging on to the bottom rung of the economy.

Florida’s Department of Economic Opportunity (Rick Scott’s name for his jobs department) houses a database of economic statistics going back to 1998, including the number of workers in the food preparation/server category who had an average entry wage of $8.47 in 2014, the lowest of all Florida job classifications that do not receive tips.

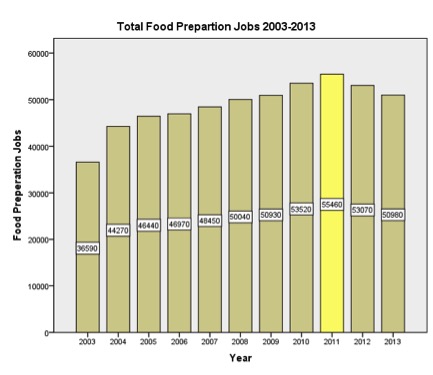

In that same year, over fifty thousand food preparer workers were in this category, out of over 7.4 million of employed workers in the state. In Figure 2, I show the total number of food preparer jobs in the total Florida workforce since 2004.

Figure 2

So what’s wrong with this graph? Notice that during the recession period (2008-2011) the number of fast-food workers increased instead of decreasing as one would expect. Like some have suggested, the fast-food industry appears to be recession proof.[v] As many Floridians’ lost either their jobs or large parts of their income they ate out less. But, when they did eat out, it was a table for four at McDonalds and not Bistro Mezzaluna.

In reality, fast-food chains did lose profits, but ate (no pun intended) most of their losses, and continued hiring new workers.[vi] To put this industry worker group in perspective, I compare the state’s total unemployment with food preparer’s percentage of jobs in Figure 3.

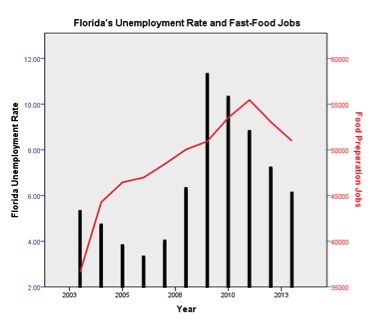

Figure 3

The black bars represent Florida’s unemployment rate from 2003 through 2013. As you can see, total unemployment reached a peak in 2009, at over 11%. The red line, in contrast, traces the total number of food preparers/servers though the same years. Notice that their numbers grew until they peaked in 2011 at nearly 56,000 workers (correlation .579, sig. <.10).

In plain terms, as people were being laid-off statewide, fast-food chains were hiring new employees and, probably, many from these laid-off workers. Who knew that McDonalds was the state’s unofficial employment bureau? From now on I am going to supersize those fries just to thank them.

Finding that higher unemployment seems to increase jobs for more low-wage food workers is not only unexpected but extraordinary. On the surface it makes some sense, since in recessions people cut back on their more expensive expenditures like fancy restaurants, but when they do decide to eat out its more likely at a fast-food alternative, at least that is the prevailing wisdom.

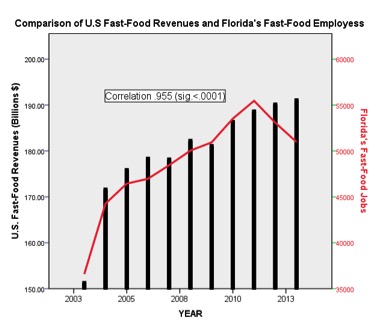

I couldn’t find any data on Florida’s fast-food sales for this period, but I did find U.S. annual revenues for this industry group. So I compared the national sales with the increase in Florida Fast-Food Jobs. Now I realize that sales in Florida will likely differ from the national data, but the upward or downward direction in revenues should be somewhat similar. As Figure 4 illustrates, it appears that these restaurants do prosper, at least in total sales, during recessions.

Figure 4

The black bars represent the total annual revenues (in billions of dollars) for U.S. fast-food restaurants from 2003 to 2013. The red-line denotes the total number of employees in Florida’s fast-food industry. Except for the last two years (2012-2013), the increasing sales on a national level correspond to increasing employees in Florida, even during the worst recession since the Great Depression. Who knew? (Well I didn’t.)

The point is that fast-food employees prospered in some perverted way (keeping their jobs and a higher minimum wage) while the rest of Florida’s workers suffered with reduced wages or layoffs. Although the recession seems to have increased fast food employment, does it also mean that increasing the minimum wage increased employment?

The simple answer is no. A rise in the minimum wage could be inhibiting this employment category’s growth. In other words, more workers could have been hired during this period if the minimum wage in Florida had not changed at all. The only way to show the true effect of raising the minimum wage on employment is to control for the effects of Florida’s economy (unemployment, GDP, revenues) and the current dollar difference between the Federal and Florida’s minimum wage.

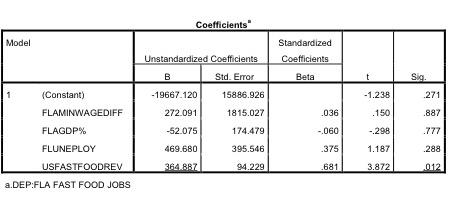

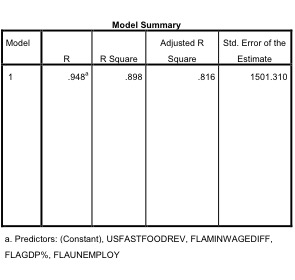

In statistics, the most common way to control for other variables is to use multiple regression (if you ever wondered why you needed to take algebra, just skip ahead). In plain language, we create a model that measures the effects of several predictor variables on the dependent variable, which in this case is the total number of food preparers in Florida.

The great part of this technique is that it allows us to keep constant other predictor variables (such as the economy), so we can see the true effect that an increase in the minimum wage has on fast-food jobs. When we control for unemployment, U.S. fast-food sales, GDP, and finally, the difference between Florida’s and the U.S. minimum wage, we find that only increasing sales has a statistically significant impact on Florida fast-food employment. (See the end-note below for the model statistics)[vii]

In other words, both the state’s unemployment rate and minimum wage differences had no effect on whether fast-food restaurants hired (or fired) employees.

It all comes down to their sales, even during a recession. The model predicts that as national sales increase by one billion dollars, Florida fast-food employees increase by 365 when controlling for the other economic variables.[viii] For our purposes here, however, increasing Florida’s minimum wage didn’t do squat.[ix]

P.S. As I was finishing this article, Wal-Mart, the nation’s largest employer, increased its minimum wage to $9.00 an hour. They also announced that it will be increased to $10.00 an hour next year. For the retail sector, at least, this is a white flag of surrender. How it will affect the fast-food industry remains to be seen.

But as unemployment declines, all businesses will have to react to the changing employment climate that gives employees greater leverage. In the meantime, I’m putting in my application in for a Wal-Mart “greeter” position….

XXXXX

[i] For a good review see “Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernable Effect on Employment,” Schmitt, John, Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2013.

[ii] “Characteristics of Minimum Workers, 2013”, Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2014.

[iii] Card, David and Alan Krueger. 1994. “Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.” American Economic Review. Vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 772-793.

[iv] These restaurant employees do not receive tips.

[v] “Good and hungry,” The Economist, June 2010.

[vi] Ibid.

[viii] In regression with multiple independent variables, the coefficient tells you how much the dependent variable is expected to increase when that independent variable increases by one, holding all the other independent variables constant.

[ix] This confirms Card and Krueger’s 1994 study of fast-food restaurants.

XXXXX

[1] In regression with multiple independent variables, the coefficient tells you how much the dependent variable is expected to increase when that independent variable increases by one, holding all the other independent variables constant.

[1] This confirms Card and Krueger’s 1994 study of fast-food restaurants.

March 2nd, 2015 at 1:43 pm

Interesting stats Jim. But I think you will admit that this only looks at one industry and is presented in a time where our whole economy got turned upside down to a part time paradigm. I do not know how the State of Florida’s unemployment stats are figured, but if they are anything like the Fed’s numbers, they cannot be trusted. If we consider the true unemployed, those who have stopped looking for work and the under-employed, many economists think the numbers should be anywhere from the low teens to the low twenties.

March 3rd, 2015 at 8:37 am

“suggests that there is little or no employment reaction to modest increases in the minimum wage”

And yet President Obama is pushing for raising the federal mimimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10 per hour. This is almost a 40% increase. The author’s charts are nice, but they do not address the President’s proposal for a massive increase.

Nice straw man, man.

March 4th, 2015 at 5:33 pm

I really like the statistics Mr. Kane. Interesting stuff